John Cassim

A kombi donated to the Nyangambe community by a safari operator Shangani River Safaris. The operator is leasing a wildlife farm owned by 181 Nyangambe community members. Owing to sound management through trainings under the Resilience Anchors the community is now benefiting from a borehole, and a omnibus for safe commuting for the school children.

In Nyangambe village, on the outskirts of the Save Valley Conservancy in south-eastern Zimbabwe, Esther Masakure, 54, starts her day as many rural women do — tending livestock, and chores including cleaning, and cooking for her four children.

However, living close to the wildlife sanctuary has come with its challenges, with lions targeting her livestock. Hyenas reportedly tracking humans, especially women fetching water or firewood.

Nyangambe, in Masvingo Province’s Chiredzi district, has long struggled with human-wildlife conflict.

In the past, Masakure lost 11 goats in a single night to a lion attack, making it difficult to sustain her livelihood.

But thanks to the Resilience Anchors, a United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-led initiative, her situation has improved.

“We were resettled here in 1993 and from that time we could not do meaningful agriculture or rear livestock due to the human wildlife conflict. At one time, I had 11 goats but they were killed in one night by a lion,” she said.

“Owing to the Resilience Anchors initiative, our community has resorted to bomas, and in the past four years, I should say, this has helped reduce lion and hyena attacks on our livestock.”

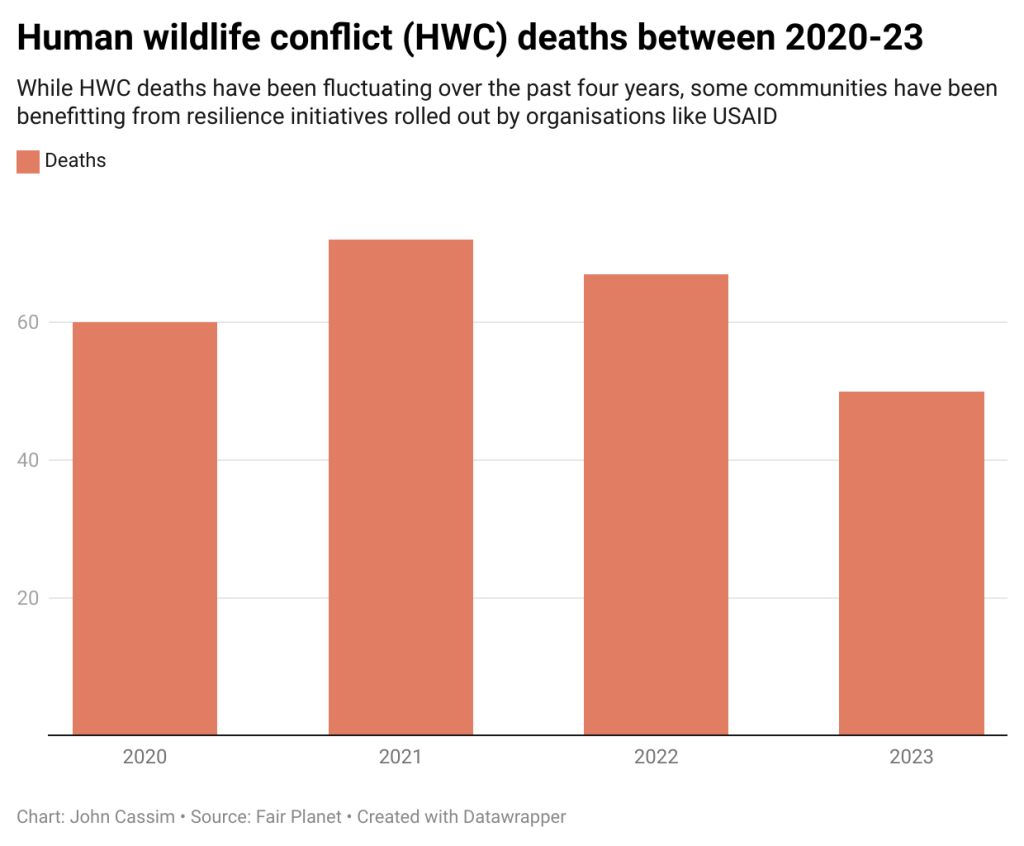

The programme, designed to enhance livelihoods in communities affected by human-wiled-life conflict, has introduced solutions that have reduced the lion and hyena attacks in the past four years.

A boma is a livestock enclosure that employs blue canvas sheets to confuse wild animals and protect the livestock.

Masakure is not alone in enjoying the benefits.

Another villager, Narvison Verandah (42) applauded various programmes that have been introduced through the Resilience Anchors.

Verandah lost his livestock to a lion attack four years ago, but today he owns eight cows and six goats.

Nyangambe village is in the agro ecological region five and receives low rainfall, making it unsustainable for rain-fed agriculture.

“Now, I am able to raise money from the sale of cattle and goats, something I could no longer do due to lion attacks,” Verandah said.

In addition to the bomas, the Resilience Anchors programme also introduced vuvuzelas and motion-sensor lights.

Masakure said: “When the lions see the light, they get scared and move away. While these innovations have helped, wildlife attacks have not stopped.

“This has prompted the erection of an electric fence to keep the wildlife in the sanctuary and better protect the community.

“The previous fence had been repeatedly damaged by elephants, creating pathways for lions and hyenas,” she added.

The USAID supports fence gardens. The employment of women as fence guardians has fostered a sense of community ownership over the natural resource management.

Nyangombe is one of the communities that is benefiting from Resilience Anchors, which has received a US$19 million investment from USAID.

The five-year community programme aims to boost livelihoods and protect biodiversity in Zimbabwe’s southeast Lowveld. The initiative supports sustainable management of water, land and wildlife resources, while also mitigating human-wildlife conflict.

Communities near Savé Valley Conservancy, Gonarezhou National Park, and Hwange-Sanyati Biodiversity Corridor have benefitted from the programme.

Data obtained from various sources including USAID has shown that 72 lives are lost every year in Zimbabwe due to human-wildlife conflict, with communities near Gonarezhou National Park alone losing an estimated US$75 000 annually in crops, livestock, and property.

To address this, USAID has trained scouts to protect wildlife in conservancies like Nyangambe and Jamanda Community Conservancies.

Verandah said: “Ten youths from our community, including my eldest son, were recruited for training and we expect them to graduate any time soon. This is part of the job creation”.

USAID-Zimbabwe mission director Janean Davis said: “This training was made possible by a partnership with Hammond Ranch in Savé Valley Conservancy.

“USAID’s project has facilitated a six-month long training for game scouts, which included team-building activities, physical fitness, survival craft, tracking, close-quarter combat, self-defence without firearms, arresting, restraint, and crime scene protocols.

“With this training, local people got jobs helping to instil a sense of ownership, and increased community participation in the conservancy’s management.

“The scouts help combat poaching and illegal wildlife trade, thereby increasing economic benefits to the community.

“This is one of the many examples of how USAID partners with the private sector to achieve biodiversity conservation goals,” Davis added.

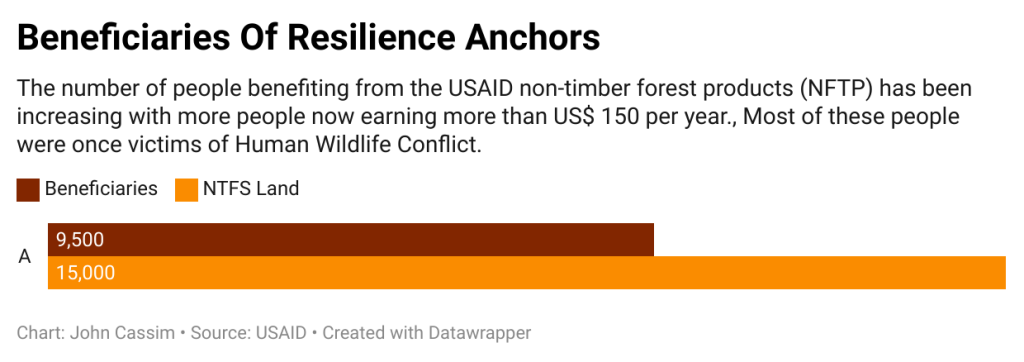

Beyond wildlife protection, USAID through the Resilience Anchors has supported sustainable natural resources management across 15 000 hectares.

In 2023, nearly 4 000 people saw increased incomes from sustainable practices like harvesting non-timber forest products (NTFPs, wild and cultivable), such as mafura seeds, marula nuts, and Kalahari melon seeds.

These products provide a valuable source of income for communities living new protected wildlife areas, with an estimated 9 500 people benefiting from the sale of NTFPs.

“When people receive tangible economic benefits from sustainable natural resource management or biodiversity conservation, they are more likely to value and support these project interventions beyond the end of the project, creating a sustainable impact,” Davis said.

“To date about 9 500 people are benefiting from harvesting and selling NTFPs which strengthens community based natural resource management and boosts livelihoods in communities adjacent to protected wildlife areas.”

A new safari project at Nyangambe that is being run by a safari operator. The proceeds from the operations are expected to revamp the community’s social and economic projects thereby giving improved livelihoods to the community members who are the owners of the wildlife farm.

Beekeeping has also been introduced as a livelihood option. Data shows that Resilience Anchors has also trained 190 community members in apiculture, honey processing, marketing, and sustainable forestry.

Each beekeeper now earns more than US$150 annually, providing additional income streams for local families.

In terms of land management, the Nyangambe community has its conservancy to a private safari operator, who has in turn provided boreholes for water and an omnibus for safe commuting for school children.

“At least 181 Nyangambe community members own a wildlife farm, which we leased to a local safari operator, who has since drilled boreholes and bought an omnibus for safe commuting for the school children,” Nhamoinesu Tinevimbo, a villager told this reporter.

“We learnt of proper land management through the Resilience Anchors hence this business move.”

ZimParks commended the Resilience Anchors initiative, stating that the introduction of collars on elephants was helping.

“We have seen the use of digital innovations such as the satellite animal collar technologies deployed in hotspots areas,” ZimParks said.

“Collaring of elephants helps us to monitor their movement and be able to tell their behaviour. We are also able to alert communities of impending dangers on time owing to this technology.”